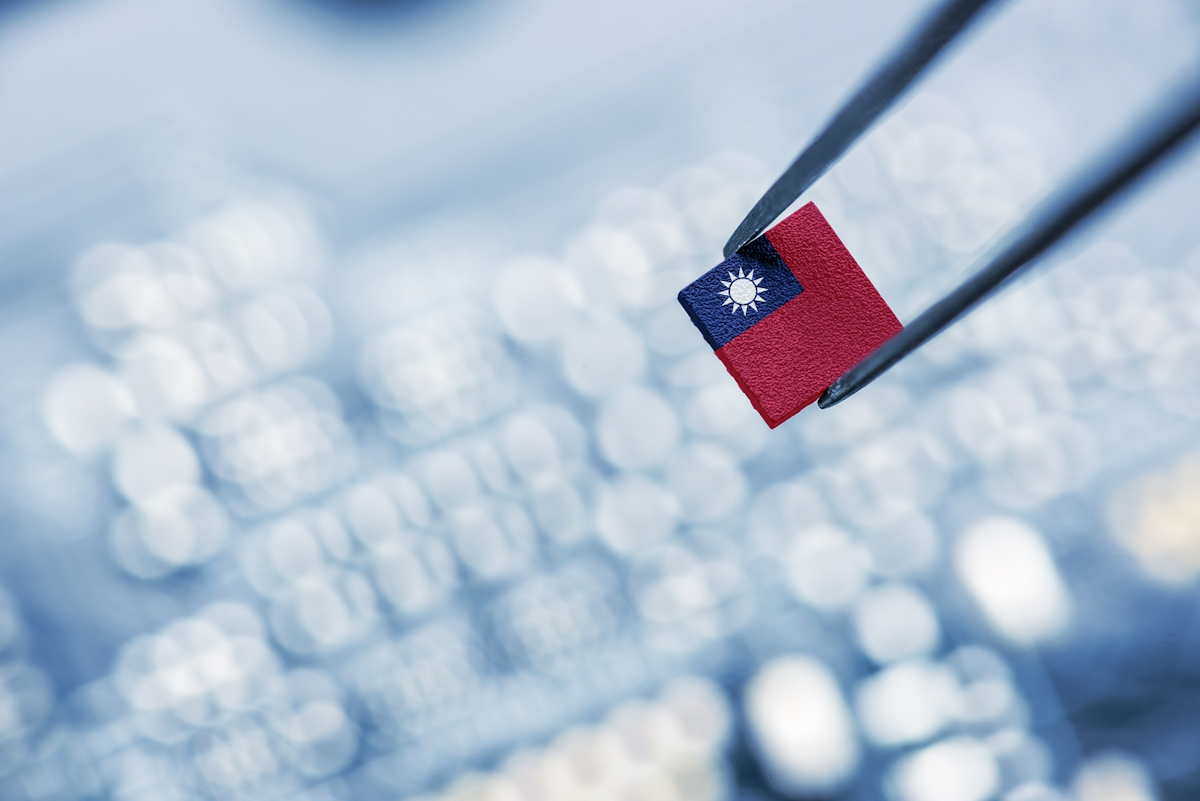

The global semiconductor industry is at a critical crossroads. While the outlook is bright due to rising demand, supply chains are being reshaped as governments around the world look to move semiconductor production to their home countries. East Asia and South Asia together account for more than 80% of global semiconductor manufacturing, according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

“This makes the world dependent on the region’s semiconductor exports and the region’s economic prospects partly reliant on the health of global semiconductor demand,” highlights the ADB.

A recent paper by Franklin Templeton highlights the semiconductor supply chain as “one of the most complex in modern manufacturing”.

Besides some Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs) like Intel and Samsung, which are involved in everything from design to production and packaging, there are several big players across the chain.

The United States dominates the fabless market with companies such as NVIDIA or Qualcomm, which specialise in chip design and development but outsource manufacturing to foundries. Asia, on the other hand, dominates the foundry sector, with TSMC and Samsung dominating. Then, there are those companies that specialise in packaging, assembling and testing the final products, so-called OSAT (Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test), with players in the US and Asia.

The concentration in Asia makes the semiconductor supply chain fragile. “Disruptions to the supply chain, whether due to natural or climate disasters, geopolitical tensions, or simply capacity constraints, can have far-reaching effects on a range of sectors and ultimately impact the broader economy and equity markets,” wrote Marcus Weyerer, Senior ETF Investment Strategist, Franklin Templeton ETFs EMEA.

He cited the supply shortage in 2021 as an example, which forced widespread production cuts among tech and automobile companies worldwide.

Decoupling from Asia’s semiconductor industry not easy

Asia’s dominance in the semiconductor supply chain has pros and cons, opines Stefan Angrick, senior economist with Moody’s Analytics.

“Massive economies of scale have driven down costs, but in this era of decoupling and derisking, governments outside the region are increasingly uneasy about industry concentration. The risks of having most of the world’s cutting-edge chips made in Taiwan – an economy regarded as a breakaway province by China – are not lost on global policymakers,” wrote Angrick in an opinion piece for Nikkei Asia.

The USA and the European Union have launched multibillion-dollar initiatives to boost the semiconductor sector, but breaking free of Asia is not that simple.

“If any country can claw back some market share, it is the US,” opined Angrick. “America still has significant chipmaking expertise and manufacturing capacity. It has also had the most success attracting cutting-edge chipmakers. For example, TSMC is building a factory in Arizona that aims to produce next-generation semiconductors within a few years.”

However, given the complexity of the full supply chain, chipmaking plants in the US will still need materials and machinery to be imported from Asia or Europe, Angrick pointed out. “Plus, US-made chips will still be shipped to Asia for assembly, testing, and packaging, at least for the foreseeable future.”

“For investors seeking to capitalize on the future of technology, understanding these regional dynamics and the semiconductor industry’s pivotal role is essential for making informed decisions,” commented Franklin Templeton’s Weyerer.

Australia

Australia China

China India

India Indonesia

Indonesia Japan

Japan Malaysia

Malaysia Philippines

Philippines Singapore

Singapore South Korea

South Korea Taiwan

Taiwan Thailand

Thailand Vietnam

Vietnam